Smartphone cancer check coming

Australian engineers are developing a low cost, easy to use cancer detector, designed to be attached to a smart phone.

Australian engineers are developing a low cost, easy to use cancer detector, designed to be attached to a smart phone.

Scientists from the University of Technology Sydney have unveiled a prototype that is not only sensitive enough to detect traces of cancer biomarkers but can quantify the level of these disease-indicating molecules, so that doctors can use this device to monitor a patient’s recovery from surgery and treatment.

“People are very familiar with the pregnancy testing sticks that use lateral flow strips. They are low cost and simple to use,” said first author Hao He.

“However this type of technology usually suggests ‘yes/no’, and occasionally a ‘maybe’, and doesn’t have the sensitivity needed for cancer diagnostics.”

“This research shows that our small hand held device can be as sensitive as large, complex and expensive instruments in the pathology laboratory.”

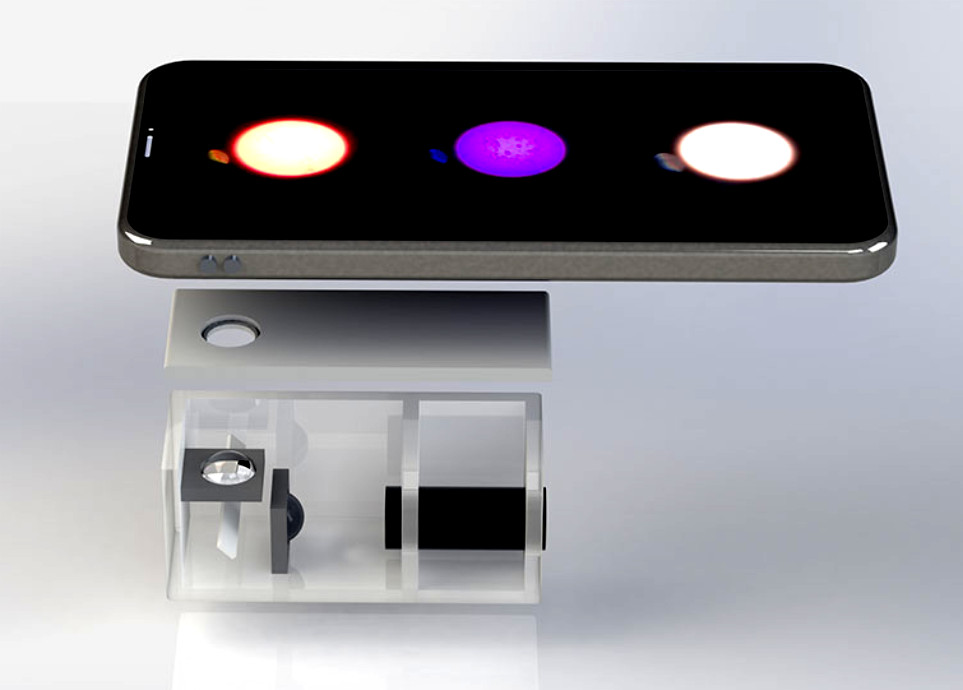

The team uses a special type of nanoparticle, highly doped with a large concentration of rare earth ions to produce an extremely bright signal on a testing strip, so that a mobile phone can be used as a detector.

A tightly focused spot by a laser pointer unlocks the brightness of the special nanoparticles.

The technique proved highly sensitive in recognising the common biomarkers indicating prostate cancer, PSA and EphA2 combined, recording new limits of detection of 89 pg/mL and 400 pg/mL respectively.

“This greatly improves the chances of picking up very early stages of cancer when the amount of biomarkers in clinical samples is very low,” He said.

“This device can also simultaneously test multiple types of biomarkers with high specificity, which will increase the accuracy, throughput and speed of testing,” He said.

The compact device takes advantage of low cost laser pointer to illuminate the bright signals and 3D-printing technologies for the housing, with a total cost less than AUD$100. Future mass production is expected to reduce costs further to around $10 per device.

“This type of research is among many other current research programs at IBMD aimed at developing easy-to-use devices that people can use at home with minimal training,” said researcher Professor Dayong Jin.

“Instead of having to travel back to hospital for tests, after cancer treatment for example, the patient simply places the paper strip in a urine sample, inserts this into the device, takes a photo of the illuminated area, and an app will upload the results for their doctor to track remotely.”

“This would make it possible for people in rural and regional areas to screen their potential risk of cancers and heart disease, once the right type of capture molecules are printed on the strips,” Professor Jin says.

Print

Print