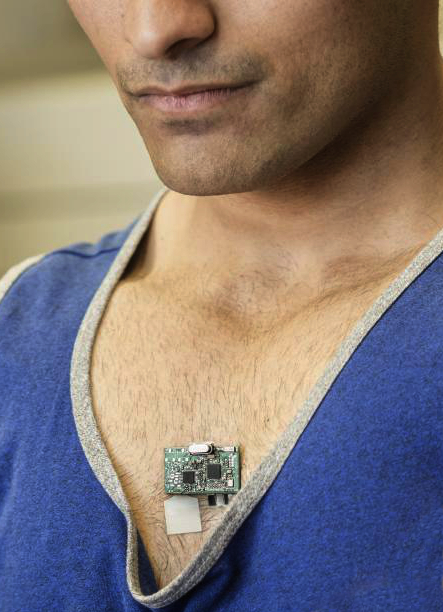

Small patch for big data on body

Engineers have unveiled an interesting new body chemical sensor.

Engineers have unveiled an interesting new body chemical sensor.

University of California researchers say the new device is the world’s first flexible wearable device capable of monitoring both biochemical and electric signals in the human body.

The Chem-Phys patch can record electrocardiogram (EKG) heart signals and tracks levels of lactate, a biochemical that is a marker of physical effort, in real time.

It is worn on the chest and is Bluetooth-enabled, so it can stream biometric data wirelessly to a smartphone, laptop or laboratory.

A team of nanoengineers and electrical engineers came together to build the device, which required a suite of sensors to be attached to a small electronic board in a compact and flexible way.

The nanoengineers worked on the patch's sensors and chemistry, while electrical engineers dealt with the electronics and data transmission.

They have published a paper on the Chem-Phys patch in the May 23 issue of Nature Communications.

UC San Diego electrical engineering professor Patrick Mercier said a major inspiration came from the universal sensors used in the sci-fi series Star Trek.

“One of the overarching goals of our research is to build a wearable tricorder-like device that can measure simultaneously a whole suite of chemical, physical and electrophysiological signals continuously throughout the day,” Mercier said.

“This research represents an important first step to show this may be possible.”

Combining different kinds of data is important, as most current commercial devices (like the approaching-ubiquitous ‘FitBit’) measure only one signal, such as steps or heart rate. Almost none of them measure chemical signals like lactate levels as well.

Having information about heart rate and lactate - a first in the field of wearable sensors - could be especially useful for athletes wanting to improve their performance. The engineers say they have already had inquiries from Olympic athletes about the wearable technologies from the lab.

Assessing both EKG and lactate at the same time could also open up some interesting possibilities in preventing or managing cardiovascular disease.

Researchers used screen printing techniques to print the electronics on a thin, flexible polyester sheet that can be applied directly to the skin.

Lactate sensors are printed in the centre of the patch, while two EKG electrodes bracket it to the left and the right.

The engineers faced a challenge in isolating the EKG sensors from the lactate sensor, which applies a small voltage to measure electric current across its electrodes.

The current used by the lactate sensor can pass through sweat, which is slightly conductive, and would disrupt the EKG measurements.

So, the researchers added a printed layer of water-repelling silicone rubber that could keep the sweat away from the EKG electrodes, but not the lactate sensor.

The sensors were then connected to a small custom printed circuit board featuring a microcontroller and Bluetooth chip, which wirelessly transmits data gathered by the patch.

The patch was tested by three male subjects, and managed to gather data from the EKG electrodes that matched data collected by commercial wristbands, and the lactate data was in line with data collected during intense workouts in other studies.

The team is now working with more sensors for other chemical markers, such as magnesium and potassium, as well as other vital signs.

Physicians have been working with the engineers to optimise the data from the various signals, and see how it correlates.

Print

Print