Graphene's great leap

A new technique could finally bring the ‘miracle material’ graphene out of the laboratory.

A new technique could finally bring the ‘miracle material’ graphene out of the laboratory.

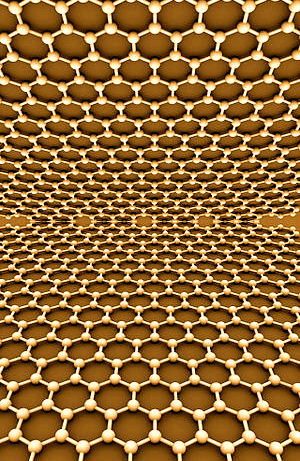

Graphene is a single sheet of carbon just one atom thick, which allows electrons pass through it with hardly any resistance at all, while remaining very flexible and stronger than any other metal.

But progress in producing it on an industrial scale without compromising its properties has proved elusive.

Now, a team of Dutch engineers say they have made a breakthrough.

The discoverers of graphene, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, famously made it by peeling graphite with Scotch tape until they managed to isolate a single atomic layer: graphene. Their work with sticky-tape won them the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics.

To make a large amount of the same substance requires a more scalable technique, a good candidate for which is chemical vapour deposition.

In the deposition process, heat is used to vaporise a carbon precursor like methane, which then reacts with a catalytically active substrate to form graphene on its surface.

A ‘transition metal’ is normally used as the substrate, but not only does the transition metal act as a support, it also tends to interact with the graphene and modify or even deteriorate its exciting properties.

To restore its properties after being grown on metal, the graphene has to be transferred to a non-interacting substrate, but this transfer process is cumbersome and often introduces defects.

A few years ago, PhD students at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands noticed something stange about graphene grown on copper.

They found that alongside the copper, some copper oxide was also present.

A graphene film appeared to have formed on the copper oxide, leading the team to wonder whether oxidised metals might leave the properties of graphene unaltered.

Three years later, the Groningen team has successfully grown graphene on copper oxide.

The researchers also report the remarkable finding that graphene on copper oxide is decoupled from the substrate, which means that it preserves its peculiar electronic properties.

The results could be far-reaching.

“Other labs need to reproduce our findings, and quite a bit of work needs to be done to optimize growth conditions,” said study supervisor Meike Stöhr.

The best case scenario would be that large single-domain crystals of graphene could be grown on copper oxide.

If this proves to be the case, then it should be possible to use existing industrial printing techniques to make all sorts of electronic devices from graphene in a commercially viable manner.

The research is published in the journal Nano Letters.

Print

Print