Baby gene change "dangerous"

There is great concern this week about reports that the world’s first genetically edited babies have been born in China.

Associated Press is reporting that the twin girls were born earlier this month.

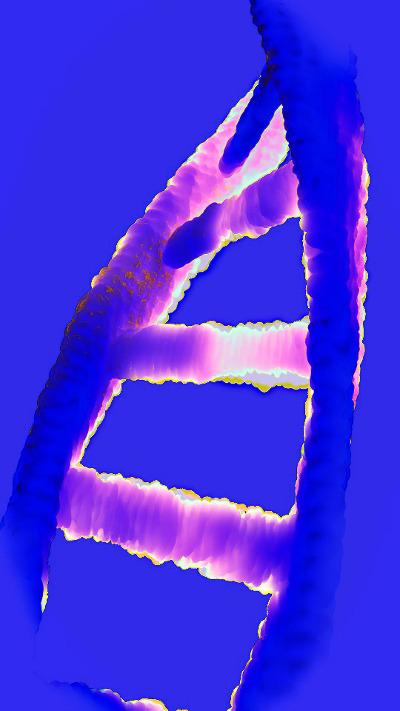

Global outcry started after the genetic scientist He Jiankui claimed in a video posted on YouTube that he had used the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 to modify a gene in two embryos before they were placed in their mother’s womb.

He said he had disabled a gene known as CCR5, blocking the pathway used by the HIV virus to enter cells.

Scientists around the world have responded with concern due to the technical and ethical issues surrounding the technique.

Professor Ernst Wolvetang - director of Cell Reprogramming Australia – has labelled the effort “unusual, unsafe, unverifiable, unethical and dangerous”.

“Unusual because ethics approval appears superficial and to have been granted after the fact, and the procedures appear to have been conducted by a company at an undisclosed location under the misleading banner of ‘vaccine research’,” Professor Wolvetang said.

“Unsafe because investigations into the off-target effects of the gene correction procedure appear incomplete and insufficient, and adverse effects later in life cannot be excluded at this stage.

“Unverifiable because the data have not been submitted to peer review scrutiny.

“Unethical because the correction itself does not actually prevent a genetic disease but rather protects against HIV infection, which itself is readily preventable.

“Furthermore it appears that even embryos that were known to have uncorrected genomes were allowed to proceed, suggesting the focus was not on health outcomes, but rather the procedure itself.”

He also said it was downright dangerous both to patients and the scientific movement.

“Dangerous because for good reasons (ethical, scientific and philosophical ones) the wider scientific community has agreed on a ban on human germline (heritable) genome engineering until it can be proven to be safe, and appropriate guidelines are agreed upon,” Professor Wolvetang said.

“Conducting human germline experimentation in this fashion is unacceptable and could create a backlash that sets the field of genetic medicine back many years.”

Print

Print